Disclaimer

This article is for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute financial advice. The author may hold positions in the assets discussed. Any discussion on jurisdiction, exchanges or custody providers reflect the author's personal views and experiences and is not a personal recommendation. Always do your own research and seek professional guidance before making investment or custody decisions.

Last Updated on July 6, 2025

Key Takeaways

- The history of gold as money begins with ancient civilizations like Egypt and Mesopotamia using it as a unit of account. The first standardised coins emerged in Lydia around 600 BC, and become the foundation for international trade across empires.

- Following Britain’s accidental adoption of the gold standard in 1717, most major nations joined the classical gold standard by 1912, creating a stable global monetary system that facilitated free trade, capital flows, and economic growth during what many consider the golden age of international commerce.

- World War I effectively ended the classical gold standard as countries abandoned gold to finance military spending through money printing, leading to massive inflation and the flawed gold-exchange standard of the 1920s, which contributed to the Great Depression and ultimately Roosevelt’s gold confiscation in 1933.

- The 1944 Bretton Woods system made the US dollar the world’s reserve currency backed by gold at $35/ounce, but decades of American monetary expansion led to foreign governments redeeming dollars for undervalued gold, forcing Nixon to completely sever the dollar-gold link in 1971.

- Since 1971, gold has functioned primarily as an investment and store of value rather than currency, experiencing major bull markets during periods of currency instability and inflation, while central banks continue holding substantial gold reserves as insurance against fiat currency risks.

- Despite being removed from formal monetary systems, gold remains important as central banks worldwide continue accumulating reserves, suggesting what Jim Rickards calls a “shadow gold standard” that positions gold as potential insurance against future fiat currency failures.

The history of gold goes back almost 6000 years to the earliest years of some of humanity’s most ancient civilizations.

While not formally part of the money system today, central banks still hold gold, giving it a proximate shadow status in the current system.

Of all the elements of the periodic table, gold is the one best suited for use as money. It is:

- Scarce

- Malleable

- Durable

- Portable

- Divisible

- Fungible

The unique nature of gold’s chemical properties is why gold has been used as money for so long and why it superseded other commodities. It was given value by the market because it functioned as money better than anything else. This is why gold coins emerged in the ancient world and were used right up until the modern fiat era.

I think the history of gold is so fascinating because its story is tied to the rise and fall of nations and empires. It’s not really a story about a yellow metal but a story about human civilization.

Gold’s key attribute is that it is a store of value over a long period of time. It can fluctuate in the short term but over decades, centuries and millennia, it preserves wealth.

As the saying goes, you don’t buy gold to get rich, you buy gold to stay rich. It is a wealth preserver.

Often people think of gold as an investment. In our current fiat system that may be true but this is not quite the most accurate way to think about gold.

Gold should be thought of as money. It is a superior and longer lasting equivalent of currencies such as the U.S. Dollar, the British Pound and the Euro.

Gold is used to buy and sell things and, more importantly today, it is used as a form of monetary savings that is immune to debasement.

| Bonus: Click here to find out about when gold was first used as money in Ancient Egypt and Ancient Mesopotamia. |

The History of Gold in the Ancient World 4000BC – 500AD

The Earliest History of Gold in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia

The earliest account of gold in history goes back to Ancient Egypt.

The Ancient Egyptians used gold as jewellery as far back as the 4th millennium BC. The Egyptians called gold “nebu,” meaning “the flesh of the gods,” and believed it was literally the skin of Ra, the sun god.

Pharaohs covered themselves in gold not just to display wealth, but to demonstrate their divine nature and ensure their successful journey to the afterlife. The most famous example of this is Tutankhamun’s burial mask, containing over 20 pounds of solid gold.

The earliest trace of gold being used as money in Egypt is the recording of the silver/gold ratio in the 12th century BC. However gold was not widely used as money in Ancient Egypt. Silver was more abundant and was therefore preferred.

We actually have a much earlier record of gold as money in Ancient Mesopotamia, with the Ebla tablets of the 24th century BC recording the silver/gold ratio, a significant moment in the history of gold.

These cuneiform tablets record detailed transactions involving gold, showing that it was already being used as a standard of value for major purchases.

The famous Code of Hammurabi includes specific laws regarding gold transactions, demonstrating how central this metal had become to economic life.

Like Ancient Egypt, silver was more dominant in Mesopotamia but we can see gold slowly start to emerge.

However at this stage precious metals were a unit of account rather than a circulating currency. Goods were priced in gold or silver but the exchange would have been done with other commodities.

At this early stage gold was also uncoined. In a non-standardised form trade with gold was inefficient as you needed to assess the weight and purity. Yet uncoined gold became a unit of account because people found it a superior form of commodity money to the various alternatives such as shells, beads and livestock.

Nevertheless despite the limitations on the use of gold in these ancient civilizations, these early developments are a critical part of gold’s history and created the foundation for gold’s later role as an international circulating form of money.

The Development of Gold Coinage in Ancient Lydia

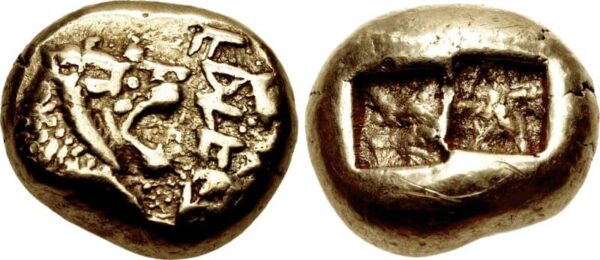

The first use of standardised coined gold as currency, the stater comes from Ancient Lydia around 600BC. The Lydian empire predated the Persians in what is now modern day Turkey.

King Alyattes minted coins out of electrum (a gold-silver alloy), while his son, King Croesus, minted the world’s first gold coinage.

This innovation was far more significant than it might initially appear – it transformed gold from something to be measured against into a standardised medium of exchange that could facilitate commerce across vast distances. With weight and purity which was guaranteed by the sovereign gold staters became the international currency of their time, accepted from Greece to Persia.

It was a significant development in the history of gold but also in the history of money more broadly and of civilization itself.

The practice of minting standardised coinage soon spread all over the ancient world, particularly in Persia, Greece and Rome, fundamentally changing how trade and commerce worked.

Today, as history’s first standardised coin, the Lydian stater is one of the most famous in the world.

Gold In Ancient Persia and Ancient Greece

Cyrus the Great conquered Lydia in 546 BC, acquiring not just territory – but control of the world’s most advanced monetary system and its gold-producing regions. The Persians quickly recognized the strategic value of gold, both as a tool of administration and a symbol of imperial authority.

Persian gold darics, first minted under Darius I around 515 BC, became the international standard for large commercial transactions. These coins maintained consistent weight and purity across the vast Persian territories, facilitating trade from Egypt to India. The daric’s design, featuring the Persian king, projected imperial power.

While the Lydians and Persians ran a bimetallic monetary system, the Greeks primarily transacted in silver. Nevertheless gold did play a role in their society.

Greek city-states developed their own distinctive coinage systems, with each polis minting coins that reflected local identity and values. Athenian gold staters featured the head of Athena and became widely accepted throughout the Mediterranean due to Athens’ commercial power. The famous “owl” coins of Athens, though primarily silver, were often complemented by gold issues during times of prosperity. Greek coinage advanced the art of die-cutting and established many design principles still used in modern numismatics.

The Greeks established trading posts throughout the Black Sea region to access Scythian gold, and Greek merchants carried gold coins to markets from Spain to India. Greek colonization efforts were often motivated by the search for precious metals, and many Greek settlements were strategically located near known gold deposits.

The Greeks also developed more sophisticated metallurgical techniques, including improved methods for separating gold from silver and testing metal purity.

The History of Gold in Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome primarily operated on a silver standard, with the famous Roman Denarius at the centre of the monetary system. However over time, as the expansion of Roman power brought unprecedented quantities of gold under their control, the yellow metal became more prominent.

While gold was used on occasion during the Roman Kingdom and the Roman Republic, it was Julius Caesar, the last leader of the Republic between 49BC – 44BC who instituted the use of gold coins in greater quantities with the minting of the 8 gram gold aureus.

The aureus circulated alongside the silver denarius and, during the time of Julius Caesar, 1 aureus was worth 25 denarii. Gold was mainly used for larger transactions by the wealthy, while silver could be used for smaller transactions by the general population.

Successive Roman emperors debased the silver currency over the next several hundred years leading to rising prices, price controls and general economic chaos.

Emperor Constantine attempted to right the ship in 312AD by issuing a massive amount of gold coinage.

His new gold solidus permanently replaced the aureus.

It was smaller at 4.55 grams of gold, however Constantine maintained the fixed weight of the solidus without debasement and managed to restore some short to medium term stability to the Roman economy.

The damage, however, was done and a combination of military overextension along with economic decline led to the demise of Rome and its eventual fall in 476AD.

Yet the gold solidus survived the fall of the Western Roman Empire and continued to circulate for hundreds of years in the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire. It is a hugely significant coin in the history of gold, not so much due to its introduction in 312AD but due its long life in the Byzantine Empire.

Read More: A Brief History of Gold Coins

The History of Gold in the Middle Ages 500 – 1500AD

The Byzantine Empire’s Continuation of the Gold Solidus

With the fall of Rome, wealth, power and influenced shifted East. First to the Byzantine Empire and then the the Ottoman Empire.

The Byzantines continued to use gold coin in the form of the solidus leading some to argue that the solidus is history’s most successful currency. To me it’s a strong argument. The coin maintained its weight, purity, and international acceptance for over seven centuries. It became so reliable that medieval merchants from London to Baghdad preferred it to their own local currencies.

The secret of the solidus’s success lay in Byzantine monetary discipline that bordered on the obsessive. Imperial authorities maintained strict controls over gold supplies and minting processes, ensuring that each coin met exact specifications. Byzantine law imposed severe penalties for counterfeiting or debasing the solidus, including death for mint officials who violated purity standards. This unwavering commitment to monetary integrity made the solidus the medieval world’s equivalent of a modern reserve currency.

Byzantine gold reserves were carefully managed through a combination of mining, trade, and conquest. The empire controlled important gold mines in Anatolia and the Balkans, while Byzantine merchants maintained extensive trade networks that brought African and Asian gold to Constantinople. Military campaigns were often designed as much to capture gold as territory, with Byzantine generals systematically looting the treasures of defeated enemies. The empire’s strategic position between Europe and Asia allowed it to profit from gold trade between distant regions.

The international influence of the solidus extended far beyond Byzantine borders, shaping monetary systems throughout medieval Europe and the Middle East. Arab rulers modelled their gold dinars on the solidus design and weight standards. Italian city-states used the solidus as the basis for their own gold coins, and even distant kingdoms like Anglo-Saxon England acknowledged the solidus as the ultimate standard of value.

The Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic conquest of gold-rich territories in the 7th and 8th centuries created one of history’s most extensive and sophisticated monetary systems. Muslim armies captured Byzantine and Persian gold reserves while simultaneously gaining control over major gold trade routes between Africa and Asia.

The establishment of the Islamic caliphates from Spain to Central Asia created a unified economic zone where gold could flow freely, fostering unprecedented commercial development.

The Islamic gold dinar, first minted by Caliph Abd al-Malik in 691 AD, became the standard currency across the vast Islamic world. Unlike the diverse coinages of medieval Europe, the dinar maintained consistent weight and purity from Cordoba to Samarkand, facilitating trade across enormous distances.

Islamic monetary law, based on Quranic principles, required that gold and silver coins maintain specific weight ratios, creating a bimetallic system that remained stable for centuries.

Islamic merchants developed the most sophisticated commercial networks in the medieval world, with gold serving as both the medium of exchange and the ultimate store of value. Muslim traders established permanent settlements throughout Africa, India, and Southeast Asia, creating trading relationships that brought African gold to Asian markets and Asian goods to African gold-producing regions. The famous medieval traveller Ibn Battuta could travel from Morocco to India using only Islamic gold dinars, demonstrating the system’s remarkable geographic reach.

The intellectual achievements of the Islamic Golden Age included significant advances in metallurgy and chemistry that improved gold processing and authentication. Islamic scholars like Jabir ibn Hayyan developed new techniques for refining gold and testing its purity, while Islamic mathematicians created accounting systems that facilitated complex international gold transactions. Islamic legal scholars developed detailed commercial law governing gold transactions, creating standards for contracts, partnerships, and international trade that influenced commercial practice throughout the medieval world.

The Re-emergence of Gold in Europe During the Renaissance

The European Renaissance witnessed a remarkable moment in the history of gold. After centuries of gold being effectively absent from the continent, it re-emerged in 1252 in spectacular fashion with the introduction of the Florentine florin.

Italian city states had grown wealthy from trade with India and China which enabled them to adopt gold as their monetary standard, as they sought to compete with Islamic and Byzantine monetary systems. This was a decision which enabled Florence to thrive as gold provided a more stable foundation for savings and investment.

Very soon the florin was the dominant currency in Europe and much of the known world. Venice and many other European cities and states followed by minting their own gold coins modelled on the florin. Banking houses like the Medici emerged and a new era of credit and trade emerged like never before.

African Gold Empires

The West African gold empires of Ghana, Mali, and Songhai controlled some of the richest gold deposits in the medieval world, creating civilizations whose wealth rivalled anything in Europe or Asia. The Ghana Empire, which flourished from roughly 300 to 1200 AD, built its power on controlling trade routes between Saharan salt mines and West African gold fields. Ghanaian rulers imposed taxes on all gold passing through their territory, accumulating vast royal treasures that funded impressive military and administrative systems.

The Mali Empire, which succeeded Ghana as the dominant West African power, reached the height of its influence under Mansa Musa (1312-1337), whose wealth became legendary throughout the medieval world. Mali controlled the Bambuk and Bure goldfields, which produced some of the finest gold in Africa. The empire’s sophisticated administrative system included royal monopolies on gold nuggets above certain sizes, while gold dust served as everyday currency throughout Malian territory.

Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324-1325 created one of history’s most spectacular displays of wealth and fundamentally altered medieval understanding of African riches. Arguablly the most significant individual figure in the history of gold, his caravan reportedly included 60,000 people, including 12,000 slaves each carrying four pounds of gold bars. In Cairo, Musa distributed so much gold that the metal’s price didn’t recover for over a decade. Contemporary Arab chroniclers described streets lined with gold, and Musa’s generosity was so legendary that European maps began showing Mali as a land of infinite riches.

The Songhai Empire, which dominated the region from roughly 1464 to 1591, continued the tradition of gold-based power while expanding control over trade routes extending from the Atlantic to the Red Sea. Songhai rulers maintained royal monopolies over gold mining and trade, using the profits to fund one of Africa’s most sophisticated military and administrative systems. The empire’s capital at Gao became a major center of Islamic learning and culture, with libraries and universities funded by gold wealth that rivalled anything in contemporary Europe.

The Age of Exploration: The History of Gold in the New World 1500 – 1800

Spanish Conquistadors and the Plunder of Aztec and Inca Gold

When Spanish and Portuguese explorers discovered the New World, they found an abundance of gold objects as well as easily mined gold and silver. This was another significant moment in the history of gold because suddenly the supply of gold dramatically increased.

The Aztecs, Incas and Mayans used precious metals but not as money. Instead they valued it primarily for its beauty and religious significance. The Spanish took their loot and transported it back to Spain, leading to a huge amount of new supply of gold and silver flowing through to both Europe and Asia.

The massive influx of gold into European markets triggered what historians call the “Price Revolution,” a period of sustained inflation that lasted over a century and fundamentally altered European economic relationships. Between 1500 and 1650, European prices increased by 300-400%, a rate of inflation over such a long period of time unprecedented in recorded history.

Spanish colonial gold mining operations in the Americas represented the largest and most systematic extraction of precious metals in human history up to that time. The discovery of major gold deposits in New Granada (modern Colombia), Peru, and later Brazil created mining complexes that employed tens of thousands of workers and extracted gold for over 300 years. These operations combined indigenous mining knowledge with European organizational methods and African slave labor to create unprecedented productive capacity.

The encomienda system became the primary method for organizing colonial gold mining, granting Spanish colonists the right to indigenous labour in exchange for supposed protection and Christian instruction. In practice, this meant forced labour in dangerous mines where death rates were extraordinarily high. Indigenous people were required to work in mines for specified periods, often in conditions that amounted to death sentences. The demographic collapse of indigenous populations in gold-producing regions reflected the brutal reality of Spanish colonial mining.

The Spanish treasure fleet system was one of history’s most ambitious attempts to move wealth across the oceans. Beginning in the 1560s, Spanish authorities organised annual convoys that carried New World gold and silver across the Atlantic under heavy naval protection. These fleets, known as the “flota,” became essential to Spanish imperial finances, carrying an estimated 16,000 tons of silver and 180 tons of gold over three centuries of operation.

The logistical challenges of treasure fleet operations were enormous, requiring coordination between mining regions, Caribbean ports, and Spanish naval bases. Ships had to be specially designed to carry heavy precious metal cargoes while maintaining seaworthiness for Atlantic crossings. The annual cycle of treasure fleet departures created predictable targets for enemy nations and pirates, leading to an arms race between Spanish naval protection and international predators.

Pirates and privateers made treasure fleets their primary targets, creating some of history’s most famous naval adventures and criminal enterprises. English privateers like Francis Drake and Dutch raiders like Piet Hein captured Spanish treasure ships worth millions of modern dollars, funding their own nations’ development while weakening Spanish power. The capture of a single treasure galleon could finance entire military campaigns or provide working capital for emerging industries in England or the Netherlands.

The economic impact of treasure fleet losses extended far beyond their immediate value, affecting Spanish fiscal planning and international monetary systems. When treasure fleets were delayed or captured, Spanish government finances faced crisis, as royal revenues depended heavily on gold and silver arrivals. International merchants and bankers learned to anticipate treasure fleet schedules, creating complex credit systems that allowed trade to continue even when precious metal supplies were interrupted. The regularity and scale of Spanish treasure transport created the world’s first truly global monetary system, but also its first global financial vulnerabilities.

The Spanish rise to power also changed the balance of the European monetary system with Spanish coinage challenging the florin for the position of the most dominant money in Europe.

While the Spanish moved significant amounts of gold to Europe, their silver production dwarfed that of gold. A 1497 monetary reform led to the issue of the Spanish silver dollar or real de a ocho, also known as pieces of eight.

Unlike the florin, which relied on European gold sources, the Spanish coin benefited from an seemingly inexhaustible supply of high-quality New World silver, enabling Spain to maintain consistent production and standardisation that made it the preferred medium of exchange across Europe, Asia, and the Americas.

With the real as the base, the Spanish monetary system created a hierarchy of precious metal coins, including gold. The most famous gold coins were the gold escudo, initially worth 16 reales, while the famous doubloon was a two-escudo gold coin worth 32 reales.

Gold’s Role in the Early U.S.A.

The Establishment of the United States

The newly formed United States faced immediate challenges in establishing monetary credibility, with gold playing a crucial role in legitimizing American currency on the international stage. Alexander Hamilton’s financial system relied heavily on gold reserves to back the young nation’s debt and establish the dollar as a credible international currency. Early American gold discoveries in North Carolina and Georgia provided domestic sources of precious metal, reducing dependence on European gold imports and strengthening national financial independence.

The Coinage Act of 1792 established the gold eagle as legal tender, creating a bimetallic standard that would define American monetary policy for decades.

American gold policy reflected broader tensions between federal authority and state rights, with various states attempting to regulate gold mining and trading within their borders. The federal government asserted control over gold discoveries on public lands, establishing precedents for mineral rights that would prove crucial during later gold rushes. Early American goldsmith guilds emerged in major cities like Philadelphia and New York, creating domestic expertise in gold working and jewelry production that reduced reliance on European craftsmen. These guilds also served as informal banking institutions, storing gold for clients and facilitating precious metal transactions in an era before formal banking networks.

The War of 1812 demonstrated gold’s importance to American national security, as British naval blockades threatened gold imports and disrupted international trade. American policymakers recognized that domestic gold production and strategic reserves were essential for maintaining economic independence during wartime. This realization influenced territorial expansion policies, as American leaders sought to acquire gold-rich regions in the West to strengthen national economic security. The relationship between gold and American expansion became increasingly intertwined, with precious metal discoveries often serving as catalysts for territorial acquisition and settlement.

The California Gold Rush of 1849

The California Gold Rush represents one of history’s most dramatic examples of how precious metal discoveries can transform entire societies virtually overnight. James Marshall’s discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill on January 24, 1848, triggered a mass migration that brought over 300,000 people to California within just five years. This unprecedented population movement created instant cities, with San Francisco growing from a settlement of 1,000 residents to a bustling metropolis of 25,000 by 1850. The rush attracted people from every continent, creating one of the world’s most diverse societies as Chinese immigrants, Chilean miners, European adventurers, and American pioneers converged on the goldfields.

The social dynamics of the California Gold Rush revealed both the best and worst aspects of human nature under extreme conditions. Mining camps developed their own informal legal systems and social hierarchies, often based on success in gold extraction rather than traditional markers of status. Women comprised a tiny minority of the population but often achieved greater economic independence and social influence than they could in conventional 19th-century society. Entrepreneurs who sold supplies, food, and services to miners frequently accumulated more wealth than the gold seekers themselves, establishing business empires that outlasted the initial gold boom.

Economic transformation extended far beyond California’s borders, as gold rush wealth flowed into national and international markets. California gold helped finance Union forces during the Civil War and contributed to American economic expansion throughout the 19th century. The influx of precious metal into global markets caused significant inflation in many countries, fundamentally altering international trade relationships and monetary policies.

The California Gold Rush was followed by the gold discoveries in Australia in the 1850s and 1860s, transforming the continent from a remote penal colony into a prosperous destination for free immigrants from around the world. This was followed by a gold rush in New Zealand that began in 1862 and transformed the economic development of a small remote country into a major international trading nation.

Other significant gold discoveries occurred in Canada, Alaska and South Africa.

The Gold Standard Era 1870s – 1971

Establishment of the Classical Gold Standard

Britain was the first country in the modern world to adopt the gold standard, although it was essentially an accident.

Silver and gold both circulated as money and the Royal Mint was charged with setting the exchange rate between the two.

In 1717 Isaac Newton, who at the time was master of the mint, set the exchange rate such that gold was overvalued relative to silver and silver was undervalued relative to gold. It was a significant moment in the history of gold.

In Europe silver was valued more highly than it was in Britain and this led to a silver flight from Britain to the continent. Correspondingly gold flowed into Britain from Europe since it was valued more highly there.

While Britain was not formally on a gold standard in 1717, Newton’s move effectively placed them on one.

David Orrell explains:

“The result was that the pound sterling switched de facto from a bimetallic standard to a gold standard, with the Mint price of gold set at £3 17s 10½d an ounce (which made a guinea 21 shillings). There it remained, with wartime interruptions, for the next 200 years; a frozen Newtonian accident.”

Britain formally acknowledged this reality in law in 1816. The 1816 Coinage Act defined the Pound as a weight in gold, 7.32238 g to be precise, rather than a weight in silver.

The United States began her existence on a bimetallic standard. Alexander Hamilton’s 1792 Coinage Act set the silver/gold ratio at 15:1.

The 1792 Coinage Act also allowed for the free coinage of gold and silver. That is, anyone could present gold and silver bullion to the US mint and have it coined into United States money.

15:1 was an accurate ratio at the time as it was very close to the market rate between the two metals. But an increase in the supply of silver over the next few decades meant that the market rate of silver declined and the government peg was overvalued.

So in 1834, the US adjusted the ratio to just over 16:1. This time they overcompensated the other way and undervalued silver, as the market rate was 15.625:1.

While this was still a bimetallic standard the 1834 adjustment also put the USA on a de facto gold standard. That was because silver flowed out of the country into foreign markets where it was closer to a fair market rate.

In 1873 the USA discontinued the coinage of silver dollars that had been authorised in 1792. This continued the de facto gold standard, although it wasn’t until the Gold Standard Act of 1900 that this became fully formalised in law.

Although there was heavy resistance to the demonetisation of silver by a vocal pocket of American society, the move to gold prevailed.

Another major power to adopt the gold standard in 1873 was Germany. Having just defeated France in war and newly unified, Germany sought to emulate Britain’s economic and imperial might and decided that the gold standard was the best way forward.

At that point Britain, the USA and Germany were all on the gold standard. For the first time in the history of gold the world was moving entirely to gold.

Given the strength of their economies, other nations followed along in adopting gold, including Russia in 1897.

By 1912 there were 49 countries on the gold standard.

Gold’s Role In Stablising Global Currencies

If a country wasn’t on the gold standard themselves then they likely held British Pounds as reserves, meaning their currencies were still effectively tied to gold.

This monetary era from the 1870s to the outbreak of World War One in 1914 is known as the classical gold standard.

Under the classical gold standard a nation’s currency was determined as a fixed weight in gold. Gold was the real money and paper was merely a substitute for the real thing.

The classical gold standard is merely one type of gold standard among several but it is what most people think about when they use the phrase.

Paper money was freely redeemable in gold, which kept the system honest as governments were restricted in how much paper money they could create.

This sound money system was a glorious era for commerce and trade as gold functioned as global money. It also encouraged high savings rates which in turn allowed for the accumulation of capital and investment in industrial expansion, financed not by debt but by real growth.

Michael Bordo describes the era, not only as significant in the history of gold but significant in the history of the world:

“The period from 1880 to 1914, known as the heyday of the gold standard, was a remarkable period in world economic history. It was characterized by rapid economic growth, the free flow of labor and capital across political borders, virtually free trade and, in general, world peace.”

Read More: The 6 Different Types of Gold Standard

The Impact of World War One on the Gold Standard

The outbreak of World War One was the end for the classical gold standard for Europe, as the belligerent powers abandoned the mechanism that restrained their currency creation.

Rather than finance the war through taxation, where their citizens might resist, governments preferred to use the inflation tax instead and print the money needed to cover the deficits that financed the war.

Of the major powers, only the USA remained on the pre-war gold standard.

Four years of war caused economic devastation for those involved and the monetary policy used to finance the war left the participants’ currencies heavily devalued.

The British pound had lost 35% of its 1914 value by 1920. The Italian Lira lost 71%, the French Franc 64% and the German mark 96%.

In 1922 a conference was held at Genoa, where the European powers determined a new monetary system for the post-war environment. Plans were set in place for a return to gold.

In 1925, Britain was the first to return to gold, with other major powers following over the next few years.

However, this was a very different system to the classical gold standard. It was known as the gold-exchange standard.

Gold was in the name, but it was not really a true gold standard.

Instead of full convertibility into gold, pounds could only be exchanged for gold by foreigners and only for a minimum of 400oz of gold bars.

Small exchanges into gold coins were prohibited.

Murray Rothbard explains:

“Under the old gold standard, the nominal currency, whether issued by government or banks, was redeemable in gold coin at the defined weight. The fact that people were able to redeem in and use gold for their daily transactions kept a strict check on the overissue of paper. But under the new gold standard, British pounds would not be redeemable in gold coin at all but only in “bullion” in the form of bars worth many thousands of pounds. Such a gold standard meant that little gold would be redeemed domestically at all. Gold bars could not circulate for daily transactions. They could be used solely by wealthy international traders.”

Rothbard elaborates on why this was done:

“The purpose of redemption in gold bullion, and only to foreigners, was to take control of the money supply away from the public and to place it in the hands of the government and central bankers, permitting them to pyramid monetary expansion upon the gold centralized in their hands.”

Gold and the Great Depression

To make matters worse, not only was the gold-exchange standard not a true gold standard but Britain returned to gold at the wrong price.

They tied their currency to gold at the pre-war price, not taking into account the massive expansion of the money supply since then.

This of course did not work.

The only way that price would have worked would have been if Britain had allowed a currency contraction.

But she did not and continued an inflationary policy.

The abandonment of the classical gold standard, the wartime inflation and the disastrous post-war return to gold all set the scene for a a crisis that would unfold in the late 1920s culminating in the Wall St Crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression.

Gold has often been blamed for causing the Great Depression and the end of the gold standard has often been credited for helping with the recovery.

But these are faulty arguments used by gold’s opponents.

Jim Rickards explains:

“Gold did not cause the Great Depression; a politically calculated gold price, and incompetent discretionary monetary policy, did. For a functional gold standard, gold cannot be undervalued (the United Kingdom in 1925, and the world today). When gold is undervalued, central bank money is overvalued, and the result is deflation. A gold standard can work fine, so long as governments set gold’s price on an analytic rather than political basis…The Great Depression was then prolonged by experimental policy interventions [that gave rise to] “regime uncertainty,” which meant that large corporations and wealthy individuals refused to commit capital because they were uncertain about regulatory, tax, and labor policy costs. Capital went to the sidelines and growth languished.”

The Federal Reserve tried to inflate its way out of the Depression that was caused by Britain.

Nervous Americans did what was their right and began to withdraw their savings from banks in gold.

A bank run began in the United States and there were bank runs in Germany and Austria as well. Gold was money and people wanted the security of physical possession.

In 1931 Germany and Austria abandoned the new gold standard. Britain also abandoned it in 1931 as did 25 other countries.

Under new President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the USA, who had stuck to the classical gold standard in 1914, finally gave in.

Read More: Did the Gold Standard Cause The Great Depression?

Roosevelt and Gold Confiscation

President Roosevelt’s actions are famous in the history of gold for all the wrong reasons.

Roosevelt put an embargo on the export of gold, made it illegal for private citizens to hold gold and raised the price from $20.67 to $35 per ounce.

It is more accurate to say that Roosevelt dramatically devalued the dollar rather than raised the price of gold.

This unprecedented action was justified as necessary to prevent gold hoarding that was undermining banking system stability and hampering economic recovery efforts, but it also represented a fundamental breach of the traditional American commitment to gold convertibility and private property rights.

This was still a gold standard in a loose sense, since the US dollar was still tied to gold, but since there was no free convertibility and citizens could not hold gold it was not a true gold standard.

Gold was no longer considered money but essentially became a reserve asset only.

The revaluation of gold to $35 per ounce in 1934 provided substantial windfall profits to the federal government while effectively devaluing the dollar by nearly 70% in terms of gold content. This devaluation was intended to stimulate exports and raise domestic price levels, reversing the deflationary pressures that had characterized the early Depression years.

The policy was controversial both domestically and internationally, as other countries viewed American devaluation as competitive currency manipulation designed to gain trade advantages at their expense. The revaluation also raised fundamental questions about government promises and monetary commitments, as the Roosevelt administration had effectively reneged on decades of official pledges to maintain gold convertibility at established exchange rates.

The Bretton Woods Agreement

The world’s monetary system changed again as a result of World War Two.

The USA’s economic standing in the world had risen after the First World War, and by the end of the Second War World they were the sole economic superpower.

The USSR was a dominant political and military force but they were financially devastated and their economy was closed.

This meant the US could essentially dictate the new rules of the game.

At the Bretton Woods conference in 1944 it was decided that foreign currencies would be tied to the US dollar at fixed rates.

This formally made the US Dollar the world’s reserve currency.

Gold still played an important role in the global monetary system because foreign governments were still free to redeem their US dollars for gold at $35 per ounce.

This meant that by holding US dollars as reserves foreign governments still had a tie to gold even if they had abandoned the gold standard themselves.

For this Bretton Woods system to work it required a lot of trust in the United States government.

Foreign governments, holding US Dollar reserves, had to trust that the US would keep their money supply stable so that the fixed rate of $35 per ounce reflected the actual market price of gold in dollars.

Unsurprisingly the US abused their monetary privilege and heavily inflated their currency in the decades following the war. Had gold traded freely on the market, the price would have been much higher than $35 per ounce.

However, the US government had pledged at Bretton Woods to redeem one ounce of gold for $35 dollars.

So canny European governments who realised that their US Dollar reserves were falling in value decided to take up this standing offer and redeem their USD for gold.

After all if the market price of gold were higher, buying at $35 made perfect sense.

This was a problem for the United States. They couldn’t accept such significant outflows of gold. But this option to redeem dollars for gold hindered their ability to print money.

They had two choices. Either they could contract the money supply and be disciplined or they could just stop allowing foreign governments to redeem their dollars for gold.

They chose the latter.

In 1968 President Lyndon B. Johnson ended the existing requirement for 25% of the money supply to be held as gold reserves. In 1971 President Nixon then ended the convertibility of dollars into gold and thus severed the last formal tie between the dollar and gold.

Nixon also devalued the dollar further by adjusting the price from $35 per ounce to $38 and then to $42.22 by 1973. That is the still the price at which gold is valued on the government books despite the fact that gold trades freely at market prices significantly higher.

Read More: How Much Gold Was Confiscated In 1933?

Read More: The End of the Gold Standard

The Nixon Shock of 1971 and the End of the Gold Standard

While it could be argued that the gold standard ended with FDR, a partial gold standard remained until Nixon severed the last links to gold in 1971.

President Richard Nixon’s announcement on August 15, 1971, sent shockwaves through the global financial system and marked the end of gold’s formal role in international monetary arrangements. It was another significant moment in the history of gold.

In a televised address, Nixon declared that the United States would no longer convert dollars to gold for foreign governments, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system and ushering in the era of floating exchange rates.

At that point the United States moved onto a fiat standard with gold freely trading at market prices. The ability to own gold was restored to Americans in 1974.

The Nixon Shock created immediate chaos in international markets as currencies began to float freely for the first time since World War II. Gold prices, which had been artificially suppressed at $35 per ounce, began to rise dramatically as the free market determined its true value.

Within two years, gold prices had more than doubled, and by the end of the 1970s, they would reach unprecedented heights of over $800 per ounce. This price explosion reflected both pent-up demand and growing inflation concerns as monetary authorities lost the discipline imposed by gold convertibility.

The Modern Gold Market: Gold as an Investment Asset 1971 – Present

A Brief History of the Gold Market Since 1971

The end of gold convertibility removed gold’s last formal function as a monetary asset and turned it primarily into a store of value commodity.

Central banks no longer needed to hold gold to back their currencies, though many continued to maintain substantial reserves as a hedge against currency instability.

The transition marked the beginning of the modern fiat currency era, where money’s value depends on government decree and public confidence rather than backing by precious metals.

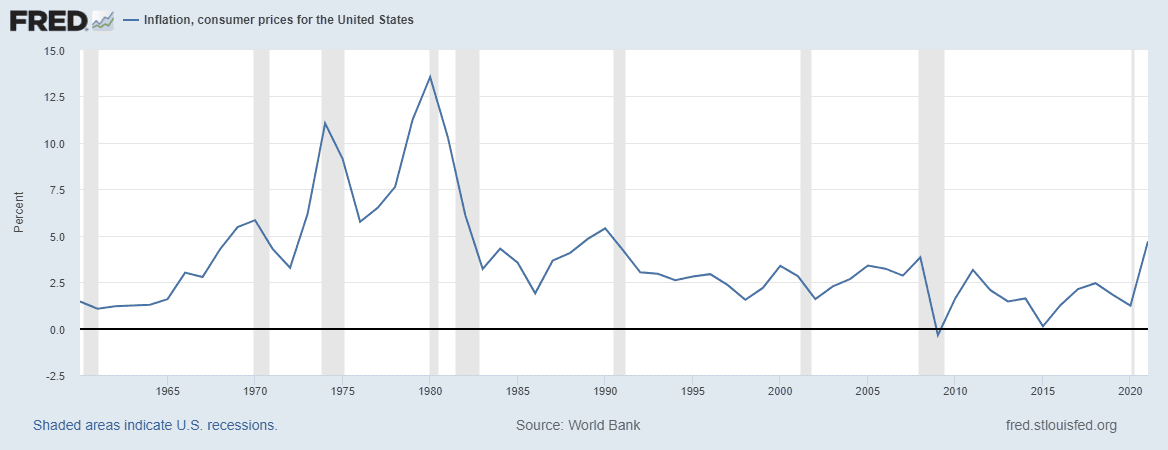

Unsurprisingly this led to massive inflation in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

As the value of the dollar declined there was a corresponding bull market in the precious metals.

The Fed managed to bring inflation under control in the 1980s and restore confidence in fiat currencies, which resulted in a prolonged bear market in gold that lasted until the late 1990s.

Some economists declared the metal irrelevant in the modern financial system. However, this bear market ended dramatically with the dot-com crash and subsequent monetary easing, which reignited investor interest in gold as an alternative store of value and inflation hedge.

A new secular bull market began in the early 2000s, which has had a few ups and downs and a short term top in 2011, but which we are still living through now.

Central Bank Gold Reserves

Central banks remain among the world’s largest gold holders, collectively owning approximately 20% of all above-ground gold supplies despite gold’s removal from formal monetary systems. The United States holds the largest official gold reserves at over 8,000 metric tons, followed by Germany, Italy, France, and Russia. These massive holdings reflect gold’s continued importance as a strategic reserve asset.

Central bank buying has been a key factor in gold’s massive move in 2024-2025.

While it seems that gold has been completely removed from the monetary system, Jim Rickards argues that we in fact on a “shadow gold standard.”

This is because of the fact that many of the world’s central banks hold gold as a reserve asset and many, including Moscow and Beijing, continue to build their position in gold.

This in effect backs their currency with gold in an informal way. The price on the Fed’s balance sheet is still $42.22, which makes it seem insignificant, but when priced by the market these holdings are substantial.

Rickards explains the significance of gold in the current monetary system:

“Countries around the world are acquiring gold at an accelerated rate in order to diversify their reserve positions. This trend, combined with the huge reserves held by the United States, the Eurozone, and the IMF, amounts to a shadow gold standard. The best way to evaluate the shadow gold standard among various countries is to use the ratio of gold to the gross domestic product (GDP). This gold-to-GDP ratio can easily be calculated using official figures and compared across countries to see where real gold power resides.”

Rickards convincingly argues that gold has never gone away as a monetary asset and is primed to make a comeback if the public loses faith in central banks and faith in fiat currencies.

“The confidence of the entire global financial system rests on the U.S. dollar. Confidence in the dollar rests on the solvency of the Fed’s balance sheet. And that solvency rests on a thin sliver of … gold. This is not a condition anyone at the Fed wants to acknowledge or discuss publicly. Even a passing reference to the importance of gold to the Fed’s solvency could start a debate on gold-to money ratios and related topics the Fed left behind in the 1970s. Nevertheless, gold still matters in the international monetary system. This is why central banks and governments keep gold in their vaults despite their public disparagement of its role.”

Read More: Why Gold Is Important To The Economy And The Monetary System

Read More: What Is The Moscow World Standard?

Read More: 8 Lessons From The Gold Bull Market In 2011

Why Buy Gold

If you accept that gold is money, suddenly there emerge a number of reasons why you may consider it wise to hold.

The fact that central banks hold gold is a tacit acknowledgement of its status as money, no matter how disparaging the rhetoric towards gold might be.

Gold has been money for thousands of years. It continues to play a monetary role today and it will almost certainly play a monetary role in the medium term future.

While Bitcoin is superior to gold and will outperform in the long term, holding gold is also insurance against the unlikely but possible failure of Bitcoin.

Here are the key arguments for buying gold:

- Gold is money

- Gold is financial insurance against fiat

- Gold is financial insurance against Bitcoin

- Gold performs well during inflation and deflation

- Gold is a store of value

- Gold allows you to remove wealth from the banking system

- Gold has no counterparty risk

- Gold is liquid

- Gold is easy to store and maintain

- Central banks will continue their easy money policies

- Central banks are buying gold

- Fiat money systems don’t last, gold does

- As the monetary system deteriorates more people will look for a safe haven

Read More: The Best Precious Metal To Invest In

Read More: What Is The Market Cap Of Gold?

How To Buy Gold For Beginners

There are four ways of investing in gold.

- 1. Physical bullion

- 2. ETFs

- 3. Shares in gold miners or royalty companies

- 4. Derivatives such as options or futures.

Physical gold is easily purchased at any number of precious metals dealerships. I use New Zealand Mint and BullionStar, which one of the many great options for gold storage in Singapore.

An ETF, such as GLD, can be purchased from your brokerage account. It gives you exposure to the gold price in a convenient way but the downside is you cannot take delivery should you choose.

You can also buy numerous gold mining companies or other ETFs that allow you to buy a diversified range of gold miners such as the GDX or the GDXJ.

Read More: How To Invest In Gold For Beginners

Read More: Offshore Gold Storage: 3 Benefits Of Holding Gold Overseas

Gold’s rarity, luster, and resistance to corrosion made it ideal for trade, ornamentation, and money. It became a universal symbol of wealth and power across many civilizations.

Gold was first used as money around 600 BCE in Lydia (modern-day Turkey), where the first known gold coins were minted. Before that, gold had value and was used as a unit of account as early as Ancient Sumer but not a standardised currency role.

If we start with Ancient Lydia then gold has been used as a form of money for over 2,600 years.

Gold became money due to its durability, scarcity, divisibility, and universal appeal. These qualities made it, more than any other commodity, most suited to the function of money.

Yes. In many ancient and pre-modern societies, people used gold (and gold coins) in everyday transactions, especially for larger purchases or trade between regions. Over time, silver and paper notes took over for daily use due to practicality.

The gold standard was a monetary system where currencies were directly tied to a fixed amount of gold. The era of the classical gold standard lasted from the 1870s – 1914.

Though no longer used in daily transactions, gold remains a store of value, hedge against inflation, and central bank reserve asset.

Conclusion

Gold has a long history and has been money for thousands of years. It is a stable asset that retains its purchasing power despite the debasement of paper currency.

Despite the shifting sands of human civilization and the rise and fall of empires, gold has retained an important role as money.

In today’s monetary system gold is almost forgotten, but it is still there. Our fiat system, with the US dollar at its centre, was built off the back of the classical gold standard as gradually the role of gold was reduced and fiat took its place.

However, central banks and governments have not abandoned gold and they retain it as monetary reserves.

As our post-1971 system runs its course and the time comes for a new system to replace it, gold will likely play a significant role.

Of course you can get ahead of the curve by putting yourself on your own gold standard by holding some of your savings in the yellow metal.

To your protection and prosperity,

Thomas

P.S. Have I left out anything important? Please let me know. Or if you found this information to be of high value, drop me a line, too. I love hearing from readers.

Sources

Bordo, Michael D. 1981. “The Classical Gold Standard: Some Lessons for Today.” Review 63.

Orrell, David, and Chlupatý Roman. The Evolution of Money. New York: Columbia University Press, 2016.

Rickards, James. The New Case for Gold. London, Penguin Business, 2019.

Rothbard, Murray N. A History of Money and Banking in the United States : The Colonial Era to World War II. Auburn, Ala.: Ludwig Von Mises Institute, 2005.

Image Credits

US $50 Gold Coin is in the public domain

Lydian Stater is licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0

Gold Aureus is in the public domain

Solidus is licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

Genoa Conference is in the public domain

Inflation Chart by St Louis Fed

Gold Chart by Trading View